5 minute read

Takeaway: Developing systems thinking begins with perspective. Go to a problem and look out. Identify the broader system that contains the thing you want to understand or first see as problematic.

Systems thinking asks us to appreciate that anything we seek to understand exists as part of a larger whole. Discipline is needed because this type of thinking requires that we resist, or at least moderate, the familiar practice of narrowing the scope of investigation into smaller units. Many never question the validity of isolating parts of a whole and seeking to understand and improve the behavior of that part viewed separately.

Functional departmentalization and functional leadership often reinforce this approach. There is a familiar, not universal, pattern among functional leaders. They often become increasingly concerned with the wellbeing of their territory and less so of the whole. They seek to optimize their patch, unintentionally sub-optimize the whole, and often find themselves in turf battles.

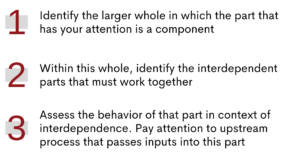

Developing systems thinking begins with perspective. Go to a problem and look out. Identify the broader system that contains the thing you want to understand or first see as problematic. Resist the draw to begin by looking into the problem by narrowing, isolating, analyzing, and fixing a part of an interdependent whole.

By adopting this perspective, you significantly reduce the possibility that your intervention inadvertently sub-optimizes the total system. It is a general principle of systems thinking that if each part of a system, considered separately, is optimized for its performance, then the whole will be sub-optimized and not operate as efficiently and effectively as you require.

What Is a System?

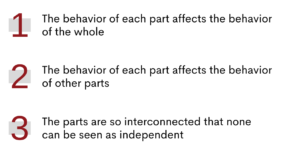

A system is a set of two or more parts that together create value that is not possible from any of the parts taken individually. There are a few conditions that define a system:

The performance of a system is based on the fit among parts in a system, not the superiority of individual parts. Dr. Ackoff (quoted above), an influential thinker on systems thinking, makes this point clear.

“Consider the large number of types of automobiles that are available. Suppose we bring one of each into a large garage and employ a number of outstanding automotive engineers to determine which has the best [fuel injection system]. When they have done so, we record the result and ask them to do the same for engines. We continue this process until we have covered all the parts required for an automobile. Then we ask the engineers to remove and assemble these parts. Would we obtain the best possible automobile? Of course not. We would not even obtain an automobile because the parts would not fit together, even if they did, they would not work well together.” (Pg 18-19)

The point is that the performance of a system depends on the interaction of the parts and the quality of their fit with one another. Your organization is subject to the same principle.

Systems Thinking

When you apply a system view to a business model, you quickly realize that a presenting symptom may well be driven by a problem elsewhere in your model. With system thinking, you must deliberately expand your field of view:

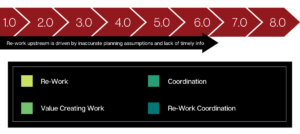

Applying this thinking to an organization with a value creating process that runs through multiple departments makes the system view and its benefits quite clear. In this example, much of the organization spends a third to a half of its time in rework. Focusing attention on any one of these process steps may create localized improvement in managing this rework, but it will miss the originating source of rework, which is the upstream planning assumptions and lack of data.

If you narrowly focus analysis and intervention on the location where you’re seeing a problem, then you will likely miss the real source of the problem. You will chase symptoms and likely alienate parts of the organization that know the upstream issues that must be resolved for system optimization.

Collaborative Methods

You can unlock the power of systems thinking by bringing the system together to do the thinking. Marvin Weisbord, a pioneer in group methods, offers further clarity by adding, “Ordinary people can use systems thinking in workplaces only to the extent they can experience the whole for themselves.” (Weisbord, 2012, Pg 304). Taken together, by using collaborative methods that include people from across the whole system and creating a full view of the relevant system, you are activating system thinking.

Collaborative methods offer another important benefit: commitment. Leaders must generally rely on members of a system to work together to implement solutions developed through collaborative process. The energy and desire to work together to implement solutions comes from commitment to something bigger than the individual. Such commitment is an outcome of a process that applies collaboration and system thinking. Leaders do well to use thoughtful strategies that promote interaction, shared understanding, and consensus decisions. It’s fun to note that the word consensus comes from the Latin word meaning, “to think together”. When people have a voice in solving problems, understand that their perspective is valued, and develop shared understanding, commitment-based implementation of agreed solutions is a reliable outcome.

Nothing Exists in Isolation; Nothing is Solved in Isolation

Systems thinking emerged in response to the limitations of machine age thinking and its basic analytic method of focusing on increasingly small parts of the whole. In the mid-20th century, problem solvers concluded that complex problems could not be disassembled into neat, pre-existing disciplines. Interdisciplinary studies emerged and their shared preoccupation was the behavior of systems.

The power of systems thinking is that it embraces the complexity of the world and accepts that the behavior of a whole is produced by the interaction and fit of the parts. Systems thinking can be activated at both individual and group levels.

Find something relatively small to improve in your organization. Don’t try to pre-think the solution. It does little good to play the role of the smartest person in the room. Pull together members of the full system. Err on the side of being inclusive. Choose those who perform value-adding work. Map the system. Identify root causes. Formulate and forecast solutions. Choose. Implement. Learn. Adjust.

You’ve just run a small experiment in unlocking the power of systems thinking. If you like what you see, apply it to your next larger opportunity.

“We might say that consensus has something to do with talking and thinking together followed by some form of agreement.” – Bruce Williams, Author of More Than 50 Ways to Build Team Consensus, c. 2007

Source note: Ackoff, Russel L., 1999, Ackoff’s Best: His Classic Writings on Management

Let’s Talk!

Dan Schmitz is a Consultant at ON THE MARK. OTM is a global leader in collaborative operating model modernization that creates real change, fast. OTM’s passion for collaborative business transformation is supported by pragmatism, systems thinking, and a belief in people that is unparalleled for 33 years.