This is the first part of our three part agile series. Read Part 2: What is a Manager’s Role in Agile?

Over the past 12 months, almost every consultancy seems to have written an article with the word agile in the title[1]. Harvard Business Review dedicated its May-June 2018 double-issue to Agile At Scale, and now here’s another one. Therefore, it should come as no surprise to any of us that the word agile has quickly become the latest buzzword for both consultants and leaders. More often than not, business leaders that we talk to will have used the word agile or not agile within the first two minutes of a conversation about the business issues that they are facing.

It is only when you drill a little deeper that it becomes clear that agile means different things to different people, and particularly means different things to different functions. To unpick this, we need to go back to the point when the word agile began to enter the business vocabulary.

A closer look at Agile vs. agile

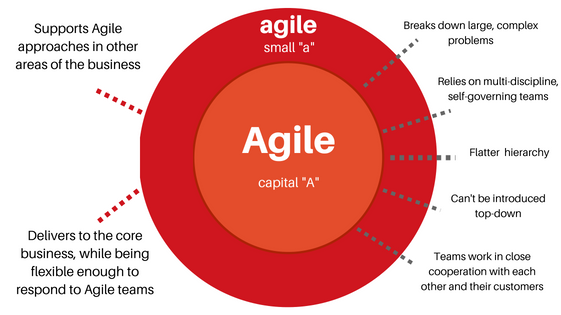

Project teams, particularly software development teams, started using Agile approaches over ten years ago as they moved from their traditional sequential waterfall approaches. Breaking down large complex problems into modules, using rapid prototyping and fast feedback loops to develop solutions for each part, and then integrating the solutions, has become the trademark Agile (note the capitalised ‘A’) approach. The capital ‘A’ Agile approach relies on small multi-discipline teams that are self-governing, working in close cooperation with each other and their customers. They are teams that fail fast (and cheap) or scale quickly, and that are accountable for outcomes rather than outputs. In this environment, the hierarchy is flatter and the role of the leader is to create the shared purpose and vision, determine the what but not the how, and then to do what they can to enable the teams to be successful.

Helping functional units to determine approaches for how to create an Agile organization should not be too difficult. We know the design criteria, and others have gone before us. We know what it is. How we help the organization redesign to an Agile approach should not be difficult to determine either, if we believe in design compatibility – the design process reflecting the end-state ways of working. If the end-state we want is Agile ways of working, then the design process must be Agile, using small multi-discipline teams that collaborate with each other and their customers to quickly develop an integrated solution.

However, the cracks begin to appear when it comes to operationalising Agile approaches. When the fast moving teams come up against the wider organisation’s management operating model, which is traditionally slower moving and more risk averse, conflict may arise. The wider organisation has decisions and authority that move through layers and across boundaries, which Agile teams see as disruptive barriers that undermine and devalue their efforts.

It is at this point that organisation design work can lose the plot if you are not very careful. The response to Agile approaches and teams coming up against a seemingly slow and bureaucratic management operating model is not to try to introduce an Agile approach from top-down across the whole organisation, not to try to create an Agile organisation. Agile approaches are not appropriate for all areas of a business, particularly more routine operations and core enabler functions.

However, these areas and functions have to support Agile teams in other areas of the business, their ways of working need to be flexible. They need to be agile with a small ‘a’, having approaches that deliver to the core business whilst still being flexible enough to respond to Agile teams when necessary. Additionally, the organisation’s management operating model needs to be agile (small ‘a’) enough to support the core business whilst also being able to respond quickly to Agile teams.

As organisation designers, what we have learnt over the past decade is:

Agile (capital ‘A’) approaches are not appropriate for all functions and can’t be introduced top-down. However, if Agile is being implemented in one area of the business, all other areas must become more agile (small ‘a’) and the management operating model must be redesigned to prevent it being seen as a bureaucratic barrier by Agile teams.

When leaders talk about agile, more often than not they are saying that they want Agile approaches and teams in one part of the organisation that can successfully tackle complex business problems (new competitors, new technologies, shifts in markets, etc.), with the rest of the organisation being agile enough to respond to the Agile teams whilst still delivering the core business day-to-day.

The use of ‘a’ and ‘A’ at the beginning of the word ‘agile’ may seem a small bit of semantics, but it has a huge impact on how to create an agile organization and approach the redesign. Designing Agile teams in one part of an organisation requires a complete redesign for the rest of the organisation to ensure that it is agile and has a supportive management operating model. This is designing an organisation that is agile.

An Agile organisation is quite different, it is an organisation made up of hundreds, if not thousands of creative empowered teams collaborating with customers to develop solutions. This is a different set of design criteria with its own design challenges. An Agile organisation is appropriate in some environments, but more often it is an organisation that is agile that meets the strategic need. Start with the end in mind.

Peter Turgoose was a Senior Consultant at ON THE MARK. OTM’s experience and passion for collaborative business transformation that’s supported by pragmatism, systems thinking, and a belief in people is unparalleled. OTM has been in business for nearly 30 years and is a global leader in organization design consulting.

[1] McKinsey: The five trademarks of agile organizations. BCG: Agile at Scale. PWC: Building Enterprise Agility. KPMG: What does agility mean for an organization?