What differentiates a successful business transformation strategy from one that hinders positive change within an organization?

How strategy is constructed is preceded by our assumption about people. In his well-known theory on management, MIT School of Management professor, Douglas McGregor argues that managers follow either Theory X or Theory Y*. While more recent thinking on leadership and management might challenge McGregor’s’ original hypothesis, as a basic framework it is a useful guide to the drivers of decision making.

- Theory X managerial style assumes that most workers are lazy, negligent, apathetic and reliant on leaders for direction.

- On the other hand, Theory Y sees workers as responsible agents acting in the best interest of the whole by taking ownership, having a desire to excel in their jobs, and being able to thrive in the right conditions.

With either perspective, subsequent design approaches will differ dramatically. Let’s take a look at what sets a successful business transformation strategy apart from the failures.

- Design with the assumption of ‘White Space’

- Control what can be controlled – be deliberate

- Place work boundaries only where necessary

- Develop multi-functional and multi-skilled jobs

- Provide information to the roles that need to take action

- Align the entire organizational system

- Design for maximizing effective work

- Integrate social and technical elements

- Ensure compatibility of design processes with design objectives

- Monitor and Govern the Design

Planning a Successful Business Transformation Strategy

In our experience, following certain guidelines leads the transformation in the right direction.

Step #1: Design with the assumption of ‘White Space’

When designing a business transformation strategy, build no more details than necessary for the organization to operate. This leaves as much “white space” as is practical. A rule of thumb that we use is to design 75%, and leave 25% for the individuals within the organization to design within the boundaries of their own roles. This enables the individuals to continue to build on the wider design framework, including filling in the blank spaces, which enables the organization to respond to emerging issues.

Step #2: Control what can be controlled – be deliberate

The ideal state for an organization design project is having a direct line of sight of all the potential variables within the organization. Additionally, you must have a way of controlling for these. On a process level, organizations make choices through workflows and process maps (end to end value streams of work). The processes highlight the changed way of meeting customer demand, and serve as the blue print for making subsequent practical changes within the organization.

The processes also exist as flows of activities across work boundaries, for example, from Team A to Team B. What’s critical is having a new design with a way of controlling any potential variances within the processes as close to where the work is done as possible. This means that corrective action can be taken before it moves from one part of the value stream to another, then ultimately to the end customer.

Step#3: Place work boundaries only where necessary

Boundaries include the time, structure, authority, and technology between teams, departments, and divisions. In an ideal world, teams should ‘own’ a whole piece of work. The more often work is handed to another team, the more likely changes within a particular team will bring in new variations.

Team changes have little impact in isolation. However, as point two above highlights, it greatly affects the whole process, impacting the quality of the end product, or increasing the amount of work within and across work boundaries. In conclusion, team changes impact the quality and potentially the reputation of the organization, or increase cycle-time and cost within the company.

Step #4: Develop multi-functional and multi-skilled jobs

A traditional viewpoint that many organization hold is that the segmentation of work leads to specialization of jobs. This is perfectly legitimate for many jobs in organizational life (think for example a lawyer or a high skilled engineer). However, often it is unnecessary and perpetuates the myth of ‘only Joe in accounting knows or can do that’. The role is so narrowly defined that they are individualized to the point of inflexibility of the work.

Where possible it is better to have multi-functional and multi-skilled roles. This is for two reasons. Firstly, it makes your organization less dependent on a particular individual for specific work outcomes, which leads to bottle necks in workflows. For example, an employee may be on leave or happen to fall sick. Just as importantly you want your workforce to remain as motivated as possible. We know from research and practice that this relates to satisfying work that involves variety. Overly specializing roles can reduce work variation and as a result boredom creeps in and motivation decreases.

In addition, narrow roles create inflexibility within the workforce, leading to additional unforeseen problems with talent and succession later on.

Step #5: Provide information to the roles that need to take action

At their heart, organizations are information processing units. Humans or machines take information from the environment and make decisions from it. Problems often occur when information is withheld or distorted between groups and managerial levels. This can lead to delays and mistakes as the required information is not with the decision-making individuals. The key point here is to avoid placing organization boundaries in ways that interrupt the critical information flow.

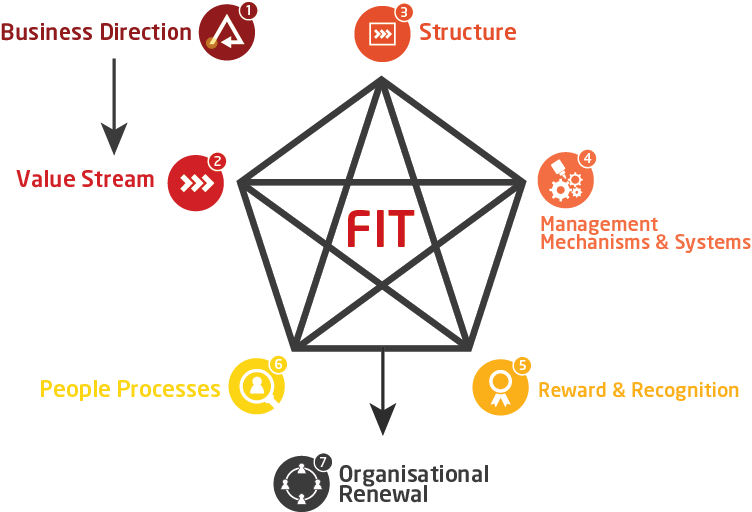

Step #6: Align the entire organizational system

The basic premise of an organization is that it is more than a management structure. An organization is comprised of a whole system of interlinking parts. At OTM we use our Applied STAR Model (shown below) to look at all parts of the organization system.

The outcome of this is the behaviors, as well as the exhibited values: how people act and behave, not just what is on the flashy management presentations.

Step #7: Design for maximizing effective work

The objective of an organization design is to provide both value to the customer and to the employees.

Research by Emery and Trist identified a set of minimal criteria that humans require in their work to find meaning. The result is beneficial outcomes for the customer:

- Freedom to participate in decisions directly affecting their work

- Access to continuous education

- Optimal variety – not too much, not too little

- Mutual support and respect of colleagues

- Socially meaningful work

- Leading to some desirable future

Step #8: Integrate social and technical elements

The key to true transformation is bringing together the social system. That is the way employees create meaningful work, which adds value to the whole. Integration also connects work to the technical elements of the organization, such as the tools, machines, and computers that are used to deliver a product or service to the customer.

It is often the case that too much attention is focused on the technical elements at the expense of the human side. As a result, there is a reduction in derived work meaning, and a resulting drop in motivation to deliver to the customer. Both are important. The social systems create meaning through the work, including the technical system. If done well, you can achieve a true transformation of a business.

Step #9: Ensure compatibility of design processes with design objectives

The starting position of good organization design is a ‘North star’. At OTM we firmly believe that this is an explicit Business Direction based on logical foundations. If part of this direction is to push decision-making down in the new organization, then this is done through the design process. For example, if you want teamwork, then you use teams as part of the redesign.

Another example is if you want to put the customer at the center of the business. Then you bring the customer into the design process rather than leaving them as a recipient of it. The design process you use aligns with the desired outcomes you are hoping to achieve. The tone you set within the design process is an indicator to your stakeholders of the behavioral expectations that the organization will have in the future.

Step #10: Monitor and Govern the Design

As with a building, structural integrity is important. For example, if you were planning on removing a wall from a house, you would check to make sure it didn’t damage the structural integrity of the whole. The house was designed as a whole system of connected parts. Changing something within potentially undermines the structure, requiring remedy or adjustment. It is the same with Organization Design.

At OTM we explicitly recommend the introduction of a Governance process to ensure that changes to the design are aligned with the original design criteria and if not, to make explicit choices to redesign from the Business Direction. This is especially so if something significant in the environment has changed, for example, a new competitor challenging you in a unseen way. We recommend to review the design alongside the annual business planning cycle. Doing so makes sure that you are keeping pace with the nature of changes required, including improvements and enhancements as well as strategic adjustments where necessary.

The house was designed as a whole system of connected parts. Changing something within potentially undermines the structure, requiring remedy or adjustment.

Why Transformations Can Fail

There is no single diagnosis for a failed transformation. Any number of internal or external factors outside of a design can bring an organization redesign to a standstill. However, there are a few common telltale signs of a business transformation strategy that lead to unwanted or unexpected results.

- Business leaders and executives were unsupportive or misaligned.

- Leaders delegated decision making and work (top-down approach).

- The self-interest was held above the collective good of the organization.

- The end-state transformation was confused with implementation.

- Transformation took a project management-driven approach.

- Implementation had frequent starts and stops, without a smooth process.

An effective strategy aligns all parts of an organization to achieve long-term business objectives. When looking at an organization through a narrow lens, some critical components can go amiss and get left out of the design phase. Instead, strategies must incorporate a collaborative, holistic approach to achieve a desired transformation.

*McGregor, Douglas. The Human Side Of Enterprise. New York: McGraw-Hill, 1960.

Stuart Wigham was a Content Manager & Consultant at ON THE MARK. In business for 28 years, OTM is a global leader in collaborative organization design and business transformation. We have a passion for collaborative business transformation that sits at the heart of OTM, supported by pragmatism, systems thinking, and belief in people.